Last month, in the wake of the appointment of Hong Kong’s new leader, the city’s securities regulator, the Securities & Futures Commission, issued a statement on the listing of infrastructure project companies, particularly in relation to the Belt and Road initiative.

For those not familiar with the term, this grand scheme is a strategy proposed by China’s National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Commerce to re-create the routes of trade and cultural exchanges that once linked the major civilisations of Asia, Europe and Africa, in what was then known as the Silk Road.

The idea is to now build a Silk Road Economic Belt and a 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, across nations from Central and southeast Asia — in other words to significantly expand the long reach of China’s influence, using its economic power.

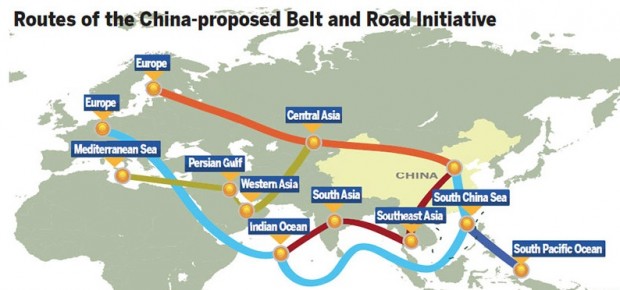

The Belt focuses on bringing together China, central Asia, Russia and the Baltic region of Europe, linking China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea through central Asia and west Asia, and further connecting it with southeast Asia, south Asia and the Indian Ocean.

The Maritime Road is in turn designed to link China’s coast to Europe through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean through one route, and the South China Sea to the South Pacific through the other.

The SFC’s statement was immediately welcomed by Hong Kong’s bourse, which added, surprise surprise, that it had actually received enquiries from companies from Belt and Road countries to list on the exchange.

Unfortunately, the SFC’s statement didn’t say an awful lot, nor did it offer much in terms of practical solutions to facilitate such listings. Its release was perhaps also politically motivated, as Chinese officials, including president Xi Jinping, will soon be visiting Hong Kong for the 20th anniversary of the city’s 1997 handover. With the Belt and Road initiative a pet project of China’s leadership, it’s no wonder the great and the good who rule over Hong Kong’s capital markets have hopped onto the bandwagon.

In short, the SFC said that a listing candidate will be required to disclose in the IPO prospectus the investment risks reflecting the nature of the project or its location. Well, that is really no different from what is asked from any other company.

It also added that applicants to listing must comply with the listing rules and requirements laid down by the exchange, which is another way of saying that, at the end of the day, they will not really be treated otherwise than other issuers.

It further said that the risks associated with infrastructure projects “may not be addressed by disclosure alone”, but that there may be mitigating factors, which the SFC might take into consideration when ruling on a company’s suitability to list.

Uphill road

Such mitigating factors could include a large shareholding by a Chinese SOE, sovereign wealth fund, substantial listed company or globally-active institutional investor, as well as sizeable Chinese or supranational financial institutions committed to providing ongoing project finance to the project, or even a direct involvement or shareholding by the government of the country in which the project is located.

This may ring a bell with readers familiar with cornerstone investors. If the big guys or, even better, state-owned players, are in on the investment, it surely can’t be all that bad.

An obvious concern here is that it could take years for an infrastructure project company to become profitable, even if it is able to secure a listing by virtue of its size and cash flow alone. In addition, many companies are structured as joint ventures to spread the risk-taking, so the regulator may rely on the involvement of state or well-known actors to satisfy itself that enough financial power or backing is behind the project.

This somehow also reminds me of IPOs by Mongolian companies in Hong Kong that were once seen as the new El Dorado for equity investors. Most have failed to materialise.

The SFC must also “obtain comfort about the availability of public and non-public information about the activities of the company in the jurisdictions in which it operates”.

This could be a long-winded exercise. From memory, it took a number of years for the regulator to satisfy itself that Russian companies were indeed fit to be listed in Hong Kong. It also remains to be seen whether institutions with mandates to invest in Asia will happily punt on stocks of toll roads or tank farms in the “stans” or the fringes of Eastern Europe. There are good reasons why Russian or Indian companies have traditionally chosen London (or, in the case of the latter, New York) as their offshore listing locations.

The biggest challenge, however, could come from the fact that infrastructure companies are, at the end of the day, dividend plays. Listing through the business trust structure would enable them to pay out up to 100% of their free cash flow, rather than limit distribution to accounting profits, which may not be forthcoming for a considerable period of time. However, only four of these have so far listed in Hong Kong, and all were also mature businesses, including HKT and HK Electric.

With Hong Kong (and indeed Mainland) investors still addicted to Chinese growth plays, listing Belt and Road issuers there could be a tall order.

Philippe Espinasse was a capital markets banker for almost 20 years and is now an independent consultant in Hong Kong. He is the author of “IPO: A Global Guide”, “IPO Banks: Pitch, Selection and Mandate”, and of the Hong Kong thrillers “Hard Underwriting” and “The Traveler”.

This column was first published by GlobalCapital.