There has been much talk over the past few weeks about the proposal by the Securities and Futures Commission to strengthen the regulation of sponsors of initial public offerings. Such sponsors, investment banks or brokers, oversee a firm’s application to list on the exchange.

The SFC wants these sponsors to be accountable for the contents of listing documents. This is to ensure that the information in IPO prospectuses is true, accurate and complete. So far, so good – what’s not to like?

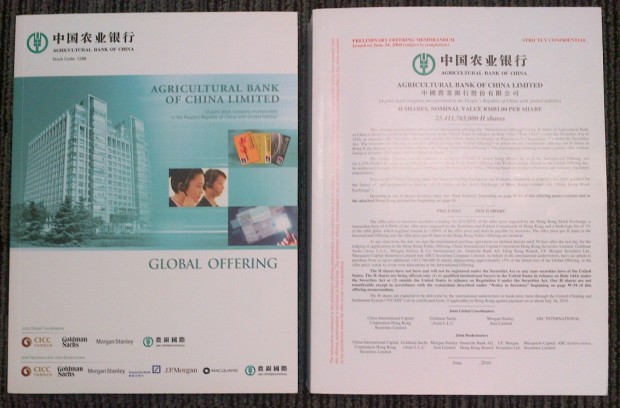

The catch is that the SFC has also proposed holding sponsors criminally liable for untrue statements (including material omissions) made in offering circulars. In other words, bankers involved in the offer documentation for IPOs could be sent to jail if a firm manages to list using false information. Certainly Hong Kong has had its share of fraudulent IPO issuers. But under the current rules, the worst that can happen to a sponsor of such a listing is the loss of its licence, as well as a hefty fine.

This recently happened to broker Mega Capital. Its licence was revoked last month after the commission found it had performed substandard due diligence on the listing sponsor of Fujian-based garment maker Hontex International. Mega was fined the not inconsiderable sum of HK$42 million.

To understand why the proposal by the SFC is such a big deal, it is important to know how a prospectus is generally drafted. And, here, size matters. For a smaller IPO, the sponsor generally holds the pen; while the company, its legal advisers, accountants and other experts, such as property valuers, chip in as part of the due diligence process to ensure the accuracy of what is described in the prospectus. The process also includes, as is required, enquiries with suppliers and customers, as well as site visits to production and other facilities. For a larger deal, following due diligence meetings on the commercial, financial and legal aspects of the business, the lawyers (generally those of the issuer) are given the primary drafting responsibility.

The prospectus is then revised while each statement in it is verified through lengthy, pizza-fuelled drafting and verification meetings that also address the hundreds of questions that Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEx) throws at the team. The truth, however, is that while sponsors are required to submit a declaration to HKEx, at the end of the day, the prospectus remains the issuer’s document. The board of directors has to sign off on its contents. The lawyers also issue opinions on what has been described. Meanwhile, the accountants will sign comfort letters which include tracing back all the bits of financial information to the company’s accounts.

But for the international version of the prospectus, the banks themselves take very little responsibility. They will generally confirm that their names and addresses appear as they are, and that the short statement on price stabilisation has been appropriately worded. By and large, that’s it. Forward-looking statements such as any earnings forecast will also be redacted.

If something goes badly wrong with the company, investors will sue the issuer, who in turn will sue the lawyers and the accountants. In fact everyone will sue everyone else. And, let’s face it, this is likely to happen in the United States more than in any other jurisdiction – which is why the banks want to have as little to answer for as possible there.

There is some sense in the SFC’s consultation paper. Banks should have more accountability when issuers are clearly defrauding investors.

But there are practical problems with the commission’s proposals too. For example, the regulator wants to limit the number of sponsors on an IPO, to focus responsibility on just one or perhaps two banks. But in my experience, it’s better for several sponsors to be involved in the process. The jockeying and outwitting of each other that goes on between the various houses working on a prospectus often results in tricky issues being covered from various angles – surely better than relying on advice from a single firm. And what if the advice from the sole sponsor is wrong?

Laying the blame for fraud so prominently at the sponsors’ door also risks deflecting from issuers’ responsibilities. The regulator might want to focus on other matters, such as the common habit of appointing independent directors only around the advance application for listing to HKEx, around 25 business days only prior to the listing hearing – if not, in some cases, even later. Independent directors should really be fully on board (no pun intended) long before a prospectus is wheeled in front of investors for the IPO marketing push.

The SFC might also want to tighten up the screening of independent directors, to make sure they are not silent partners of the chairman or CEO , as is on occasion the case.

A little more accountability is in order when aiding and abetting is invoked. But, ultimately, issuers remain the source of the fraud – and that is where the focus should be

Philippe Espinasse, a former investment banker, is the author of “IPO: A Global Guide” (HKU Press).

[This article was originally published in The South China Morning Post on 28 May 2012 and is reproduced with permission.]

(c) 2012 South China Morning Post Publishers Limited, Hong Kong. All rights reserved.