Everyone knows that Hong Kong’s IPO market is going through tough times. New deals are rare, depriving punters of a once favoured way of betting on equities and generating quick gains.

What is less appreciated, however, is the extent to which arcane practices on cornerstone investors hold back primary issuance. To understand this point, it’s helpful to compare Hong Kong’s new listings with Malaysia’s. In the year to date the Kuala Lumpur exchange has been the most active for IPO fundraisings in Asia excluding Japan, and Bursa Malaysia also claims the year’s three largest listings. Hong Kong, which in the past decade used to routinely grab the top spot among global bourses for IPOs, now trails embarrassingly behind it.

Why? Support for new listings in the form of orders from domestic and state-led institutions explains some of Malaysia’s success. But Malaysian IPOs have also been a lot more successful in gathering support from cornerstone investors, or accounts that commit to buying a big piece of a float at the offer price, ahead of formal deal marketing.

Why not always a guarantee of success, cornerstone orders can be essential to creating momentum for a deal, reassuring other investors that an offer is well supported and – generally – that it won’t tank when it starts trading. The last sizeable initial public offering in Hong Kong managed to secure only two cornerstone investors. By comparison, the last two flotations in Malaysia included 22 and 16 respectively.

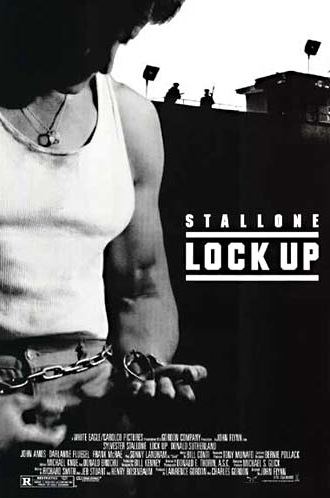

Malaysia takes a more flexible approach than Hong Kong in the ways cornerstone accounts can enter an IPO, particularly when it comes to lock-ups. A lock-up commits the issuer and its main legacy shareholders to holding their shares for a set period after IPO, usually for six to 12 months. This is to ensure that they do not issue or sell stock soon after the shares start trading, potentially triggering a big fall in price. When also imposed on cornerstone investors, a lock-up is clearly a negative for these accounts. Fund managers do not want to go to their investment committees with deals that will require them to potentially sit on their positions for a solid six months, particularly with the tendency in recent years for big global crises to engulf markets.

In Hong Kong, cornerstone investors must accept a lock-up restriction in exchange for the privilege of receiving a large, guaranteed allocation in an IPO. But not all markets are this way. Singapore requires no lock-ups on cornerstone orders for its IPOs. Malaysia used to require lock-ups as a matter of common practice, but it is now easing its requirements.

For example, in the US$2.1 billion IPO of hospital operator IHH Healthcare, which was listed in both Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, each of the 22 cornerstone accounts (a global record) only had to abide to a six-month lock-up on that portion of their order that was greater than 50 million shares – about US$50 million. Similarly, in the more recent US$1.5 billion IPO of pay-TV company Astro Malaysia, each the 16 cornerstones was only locked-up above 15 million shares – or about US$15 million – and for three months only. The easing clearly helps to lure in cornerstone support. In both cases a large number of institutions came in at the offer price well ahead of the formal launch of the deal. One might look at Hong Kong’s sleepy IPO market and wonder if it could likewise benefit from such easing for its lock-up requirements.

Relaxed lock-up rules would draw more cornerstone accounts into IPOs, resulting in more heavily subscribed deals, giving more issuers added confidence to come to market. This in turn would provide the public with more opportunities to invest in these transactions. The alternative is often weakly subscribed deals that barely make it to pricing, and which trade thinly or down at listing. Lock-ups also create an overhang effect. The market usually expects a number of big cornerstone investors to start selling all or some their stock as soon as the lock-up expires, and in turn for these large blocks of shares to depress the share price.

As it stands, imposing a lock-up on cornerstones means fewer IPOs are actually making it to launch in Hong Kong. There’s little point in imposing a ban on share sales if there is nothing to trade in the first place.

Now is probably a good time to rethink our well-meaning, but unfortunately outdated, rulebook.

Philippe Espinasse, a former investment banker, is the author of “IPO: A Global Guide” (HKU Press).

[This article was originally published in The South China Morning Post on 29 October 2012 and is reproduced with permission.]