What a difference a few years can make. Initial public offering volumes are sharply down in Hong Kong, while some markets in Southeast Asia appear to be enjoying a revival not seen since the 1997 financial crisis. I have mentioned earlier in Money Post on July 2 that much of this is due, at least in part, to the shrinkage of deal flow from China’s giant state-owned enterprises, which has generated much of the steady fee income for IPO bankers since the mid-noughties.

However, not only have IPOs in Hong Kong become fewer and smaller, but their quality has, on average, arguably also headed south. There are several reasons for this.

A small deal requires as much, if not more, work than a large one – but obviously for a smaller commission pool. This, together with fee erosion driven by low supply has in turn translated into a drop in the quality of bankers handling the deals. Simply put, they can lack experience, leading to failures to spot an issuer’s shortcomings. And even when these are known, they may lack the ability to communicate these facts to investors in a way that informs but keeps the deal together. In other words, if you pay peanuts you get monkeys.

With the supply of IPOs drying up, banks have also been forced to chase deals they wouldn’t have considered before. When I was an IPO banker, in the early 1990s the firm’s underwriting committee would not touch any flotation bringing in fees of less than US$2 million. Few banks today can afford to be so sniffy. Instead, bankers are going for a brutally pragmatic approach of bringing pretty much any deal to market, regardless of its flaws, and move on to the next if it fails. Greed and opportunism have taken over from impartial advice and putting clients’ interests first.

According to the Securities and Futures Commission’s website, there are 86 houses authorised to act as IPO sponsors in Hong Kong, up from 78 in October 2011. Compare that to Singapore, where only 44 firms are licensed to work as issue managers (Singapore’s version of an IPO sponsor).

Now, with only 81 newly listed companies in Hong Kong in 2011 (and that includes 12 that transferred their listing from the Growth Enterprise Market to the main board), and with the same established firms working on the larger flotations, many of Hong Kong’s IPO sponsors rarely get a chance to do a deal. When these smaller brokers do get involved in an offer, recent scandals suggest they can lack experience to handle an aggressive client, or take a corner-cutting approach to due diligence.

The issue doesn’t really apply to the bulge bracket firms, although they have sponsored their share of bad (and in some cases outright fraudulent) IPOs. The SFC’s move to build a more disciplined regime for IPOs and their sponsors is therefore welcome.

It’s a shame, though, that Hong Kong doesn’t seem to be heading the same way Singapore does. From August 10, Singapore will increase the thresholds for main board applicants, almost doubling the minimum market capitalisation requirement to about US$120 million, and increasing tenfold the requirement for annual pre-tax profits made in any given year to almost US$8 million. By contrast, issuers in Hong Kong can readily secure a main board listing with a capitalisation of less than US$26 million equivalent, and profits of less than US$2 million per annum. At those levels, the difference between the exchange’s two boards becomes rather blurred.

When these deals get done, the consequences are often diminutive aftermarket trading volumes, no sell-side research following, and extreme share price volatility. Add to that the recent trend for club deals, where large chunks of IPOs are taken up by corporates, strategic investors and friends and family shareholders, and it’s no wonder that investors are shunning new listings for placements or block trades – or look at other markets.

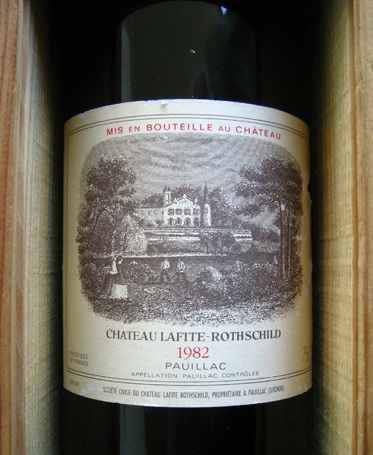

Quality breeds quantity. Discard the Yellow Tail – we want the Lafite back.

Philippe Espinasse, a former investment banker, is the author of “IPO: A Global Guide” (HKU Press).

[This article was originally published in The South China Morning Post on 30 July 2012 and is reproduced with permission.]